How to Value a Company: 3 Key Methods

The sale of a business is a momentous decision—often the culmination of decades of hard work and sacrifice. Determining the company’s value is a crucial first step in the process. Realizing a liquidity event to monetize the value of a company can be a life-changing occasion for the owner, their family, and future generations. Many business owners have a substantial portion of their wealth tied up in their business, making an optimal exit all the more meaningful.

Prior to preparing for a sale, it is essential to have a strong grasp on the true value of the company and what a buyer may be willing to pay for it. This article dives into the most common benefits and challenges of the following three methods for determining company value:

Three Key Methods for Valuing a Company

- Precedent Transactions Approach – Comparing company revenue and EBITDA against the revenue and EBITDA multiples of similar companies that have been acquired.

- The Public Company Comparison – This method leverages publicly traded valuation multiples to approximate the valuation of a privately-owned business in the same sector.

- The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) Method – This approach is based solely on the forward-looking internal finances of a company. A DCF analysis involves projecting all the future free cash flows of a company and discounting them to their present value.

While valuation methods serve as a helpful foundation for approximating the potential purchase price of a business, various other forces will affect the ultimate transaction value. Market conditions, perceived operational synergies, growth projections, and the type of deal process are among the primary drivers of the final purchase multiple paid for a company. When working with an investment bank, the deal team will utilize all three valuation methodologies, as well as their knowledge of current market drivers, to identify a probable value range for the company.

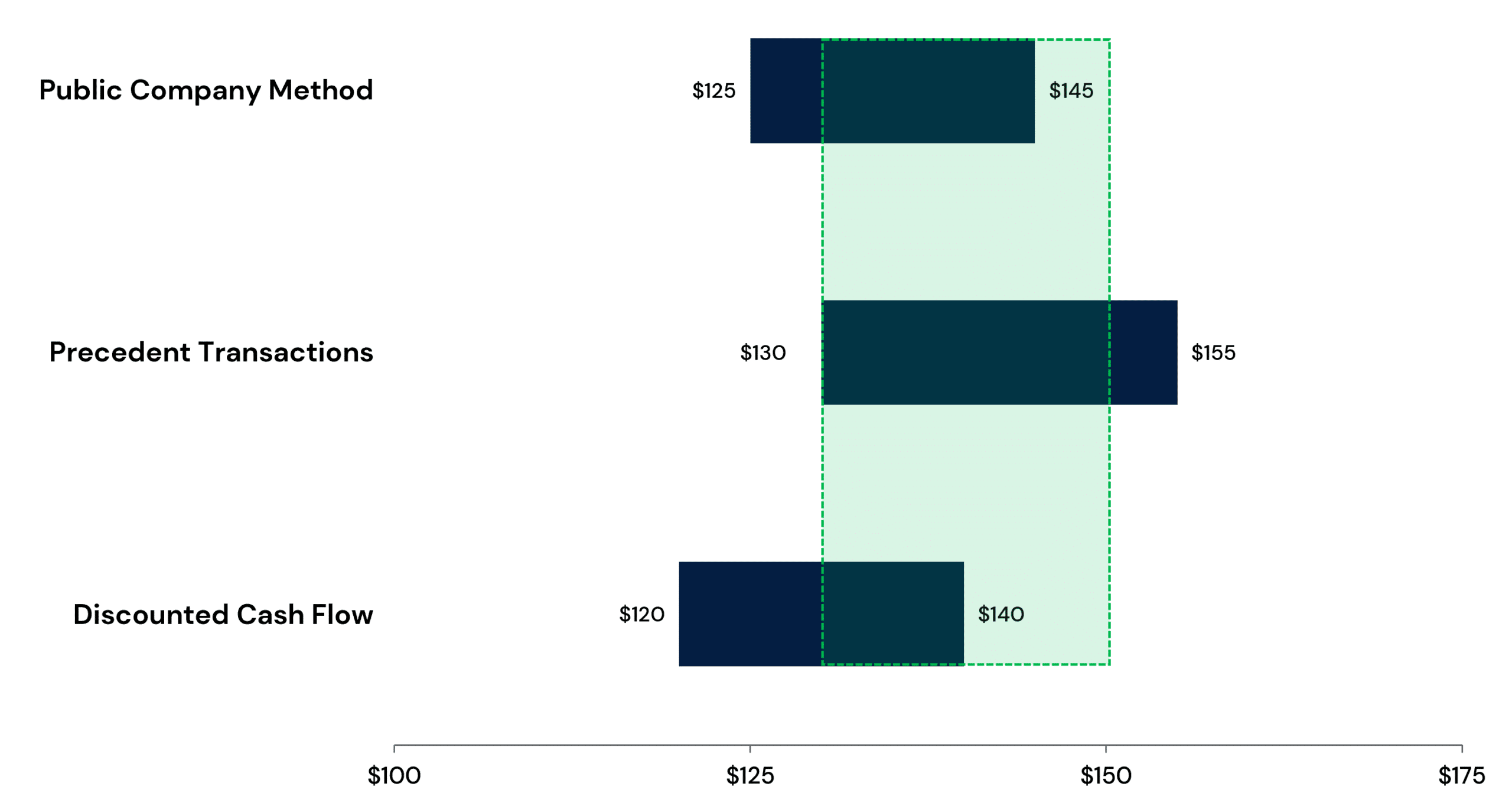

This allows the prospective seller’s transaction team to present a robust and defensible company valuation to potential buyers in an M&A process. A hypothetical valuation is depicted below, illustrating points of overlap between the three methods where a deal team may feel the true dollar figure or multiple that a buyer would pay for the company lies.

Company Valuation by Method

Source: Capstone Partners

Common Valuation Metrics Explained

Before diving into the benefits and challenges of each valuation method, it is important to take a step back and define some of the more common metrics used to assess a company’s value, profitability, and potential acquisition price. These measures allow a business owner, advisor, or potential buyer to compare a company’s value to industry peers or transactions of similar companies. Three common questions around valuation terms include:

- Enterprise Value (EV) is a measure of a company’s value. EV is calculated by summing the value of a company’s equity, debt, any minority interests, and subtracting cash. EV is often considered the theoretical takeover price of a company as it adds the debt a buyer would have to take on and removes the cash they would receive in the purchase.

- EBITDA is a measure of a company’s profitability and is a proxy for cash flow, as it ignores any effects of financing and accounting decisions. It is often useful in comparing profitability between companies, especially as a ratio. EBITDA stands for “Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation and Amortization” and is calculated with the following formula:

EBITDA = Net Profit + Interest + Taxes + Depreciation + Amortization

- Revenue and EBITDA multiples are two ratios commonly used to compare similar companies and their overall takeover value. Essentially, they answer the question, “How many times revenue or EBITDA do we have to pay to buy this company?” The EBITDA multiple is generally more widely used, particularly for profitable, mature companies. However, early-stage companies or those with high levels of recurring revenue, often in the Technology sector, are typically valued off a multiple of revenue for more meaningful comparisons.

Method #1: Precedent Transactions Approach

One of the most effective ways to establish a company valuation is to compare it against the revenue and EBITDA multiples buyers have paid for similar companies—known as the precedent transactions approach. Having tangible evidence that shows what buyers paid for similar companies is a great foundation for determining an approximate valuation and serves as bargaining power when negotiating with prospective buyers. The procedure itself is quite simple and straightforward: research previous transactions for similar companies and their corresponding financial terms. However, the similarities between the companies analyzed in this valuation approach and the company being valued is key. If the comparable transaction set is comprised of companies with different growth rates, gross margins, size, geography, or time periods than the company in question, this may lend to an inaccurate valuation.

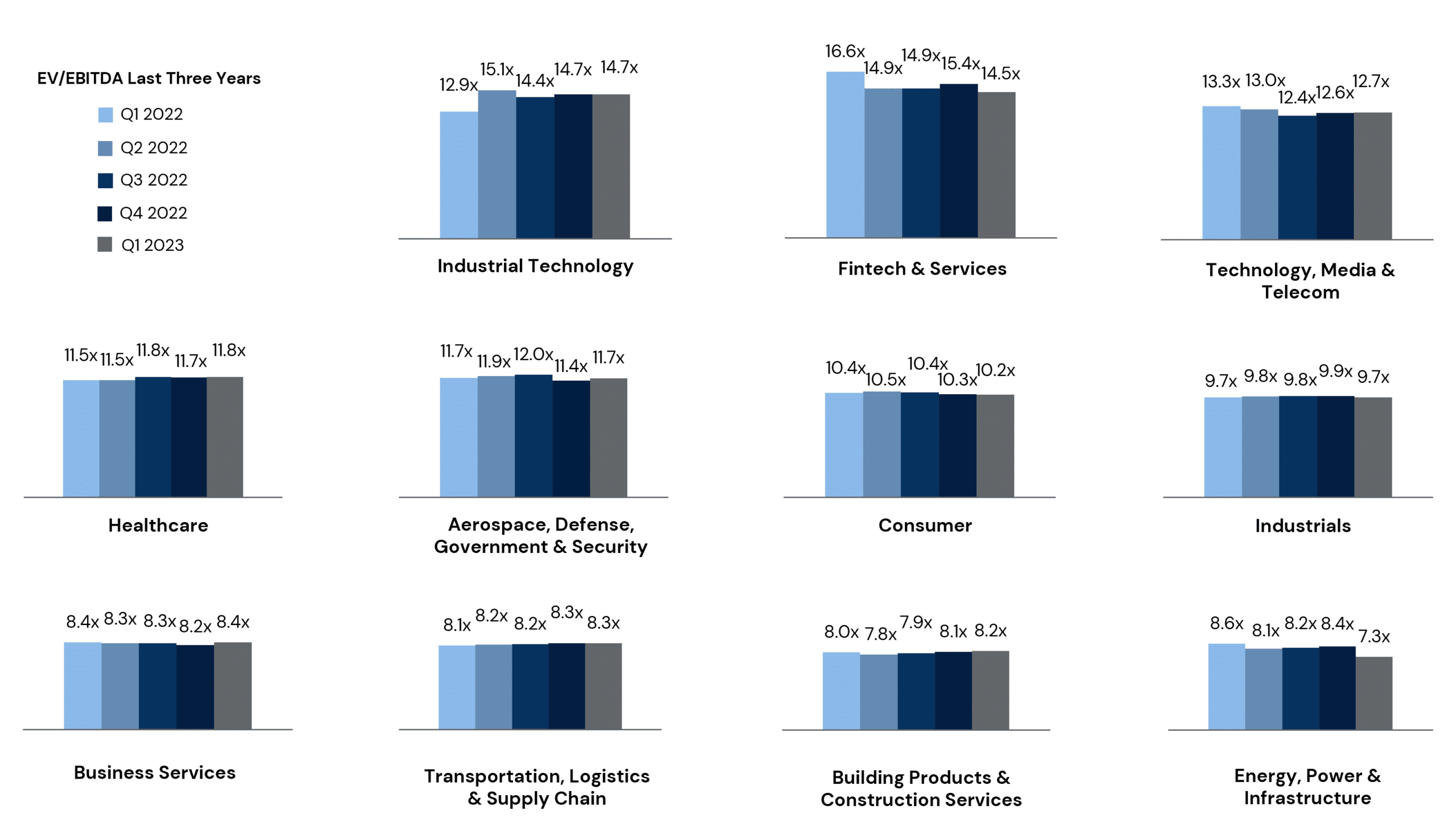

In the middle market, there is often a lack of merger and acquisition (M&A) pricing availability due to the confidential nature of transaction terms. Capstone’s Industry Insights offer sector-specific valuation analysis and benchmarking, supported by our robust M&A databases and unique banker perspectives, to provide a level of transparency into the market. Additionally, Capstone’s Middle Market M&A Valuations Index, which breaks down average revenue and EBITDA purchase multiples by industry, can also serve as a helpful resource for business owners in determining the approximate valuation range for their company.

Average EBITDA Multiples by Industry

Source: Capstone Partners

Once equipped with a robust set of precedent M&A transactions with disclosed valuations, an average or median value can be calculated to provide a sense of where a specific company may trade. For example, if similar companies are being sold for an average of 8x EBITDA and the company under examination has $20 million in EBITDA, this would equate to an enterprise value of approximately $160 million.

Key Benefit – Ease & Simplicity

The precedent transactions approach is primarily useful because of how easy it is to compare transactions. An analysis of precedent transaction valuations can identify the average multiples for an industry, what companies have been offered premium/discounted valuations, and whether strategic or private equity buyers are offering premium valuations.

Main Hurdle – Data Availability

Unfortunately, this approach is limited by the lack of disclosed financial information shared by private companies. While this includes data on revenue and EBITDA multiples, other financial information such as margins, growth rates, and leverage ratios are also important when analyzing valuations. More subjective information such as buyer objectives, potential synergies, and strategic fit are also factors. While lack of information is a significant hurdle, the precedent transactions approach is still a very useful tool for determining a benchmark valuation.

Method #2: Public Company Comparison

With a wealth of financial data available for public companies, the public company comparison method thrives where the precedent transactions approach struggles. This method leverages publicly traded valuation multiples to approximate the valuation of a privately-owned business in the same sector. Of note, public company multiples do not include control premiums, which are typically reflected in M&A transactions, and sometimes may need to be discounted to account for the larger size of public companies.

Key Benefit – Data Availability

10-Ks, 10-Qs, 8-Ks, Schedule 13Ds (and more) are all reports mandated by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and contain an abundant amount of information on public companies. Not only do they allow business owners to distill information on revenue and EBITDA multiples, but they also provide a deeper comparison between valuations of public companies and a potential valuation of privately-owned company. Historical information on growth, margins, and other metrics offers a benchmark that a business owner can compare against their company.

Main Hurdle – Comparability

One complexity of deriving a valuation from public company data is that it is difficult to compare smaller, private companies to public industry leaders who often have multiple, distinct subsidiaries. A privately owned outdoor recreation company considering a sale may look to Yeti (NYSE:YETI) as a proxy for a valuation. However, Yeti not only has an enterprise value in excess of $2 billion, but also a nationally recognized brand with a strong margin profile. It is unlikely that a business under $500 million in enterprise value would achieve the same valuation level as a large public company with significant scale and brand leadership.

Method #3: Discounted Cash Flow

Unlike the other two approaches, the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method is based solely on the internal finances of a company and, as such, is considered more of an academic exercise (one that all buyers will do). At its core, a DCF analysis involves projecting all the future cash flows of a company and discounting them for their value today.

The intricacies of a DCF can be complex, often the responsibility of the investment banking advisor representing the client pursuing a sale.

Key Benefit – Intrinsic Value

Although highly academic, a DCF analysis offers the closest estimate to a company’s intrinsic value and is widely used in the Investment and Financial Services industries. This is helpful because the other two methods derive a valuation through external comparisons, which are inherently imperfect because no two companies are exactly the same.

Main Hurdle – Assumption-based

The reason DCFs are considered academic is because they are heavily based on theoretical assumptions. Fundamentally, it is very difficult to project free cash flows for a year or two from now, let alone five years in the future. Minor adjustments to growth rates, expenditures, and margins will significantly affect cash flow projections and ultimately, a company’s fair value. In order to compensate for these variations, analysts typically develop a customizable DCF model and perform a sensitivity analysis that returns a range of valuations based on various discount and growth rates.

When to Get a Professional Valuation

No matter which method, or combination of methods is used, the golden rule stands true: A business is only worth as much as someone is willing to pay for it. A healthy pool of potential buyers fosters competition in a deal process—often driving up the valuation of the target company. Selecting the right investment banking partner, one who is knowledgeable and well connected in a specific industry, can have a significant impact on the final outcome of a sale process.

To learn more about how to properly value a company or navigate the early stages of preparing for an M&A sale process, please contact us.

Insights for Middle Market Leaders

Receive email updates with our proprietary data, reports, and insights as they’re published for the industries that matter to you most.